My dear friend Fuad Nahdi and I have had many chats over the years about the need for Muslims living in the West to have a sustained strategy of civic engagement and the meaning of radical activism.  I admire his dedication and wish I had some of his excitement and enthusiasm.

I admire his dedication and wish I had some of his excitement and enthusiasm.

He being in London and me in Toronto has not prevented us from talking at length about our daily struggles to balance instinctively left-leaning reactions and deep felt pain at the injustices we’ve been fortunate to chronicle as journalists against the teachings of a faith that demands compassion and love.

When Fuad left Mombassa, Kenya to study in London he was older and wiser than when I migrated from Georgetown, Guyana to Toronto. In the last three decades we’ve gotten married, raised families, established careers and jumped waist high into the turbulent politics of Muslim community affairs.

How we’ve managed to find and stay on the “middle path” is not really a mystery. We both came from homes where parents and elders were involved in our lives. We were raised in communities of faith that were real, not imagined. We both had teachers who taught us wisdom and didn’t lecture us with fire and brimstone speeches.

We might not have known much about Sufis, Salafis, Deobandis or Barelwis growing up, but we knew that being Muslim meant we had to be good to our neighbours and those less fortunate. This understanding, call it a firm grounding of faith and civic identities, eventually made us as comfortable in our newsrooms as we were in our local mosques. And although poverty was our lot as young men we never aspired to roll with the rich and live the high life.

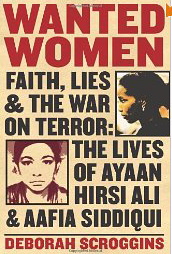

These thoughts about Fuad and I came to me as I got to the end of Deborah Scroggins book “Wanted Women: Faith, Lies and the War on Terror – The Lives of Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Aafia Siddiqui.”

Nazim's Blog

Meditations of a Muslim journalist on the shores of Lake Ontario